When Lokah: Chapter 1 dropped, we met Neeli, Chathan, and Odiyan. But behind all of them, one name kept surfacing — Who is Moothon (With Mammootty voice over). A mysterious power controlling immortals, never shown, only hinted at. So, who is Moothon?

To answer that, we need to look beyond Kerala’s Aithihyamala. From the film’s title card itself, there’s a hint pointing towards ancient Mesopotamian myths, where gods, aliens, and immortals often overlap.

While explaining the flashback, we see child Neeli looking at a cuneiform text — the wedge-shaped script of ancient Mesopotamia — carved inside the cave.

This links the beheaded idol that Neeli sees to Ishtar, the Mesopotamian goddess.

So, this mesopotamian connection makes sense.

But let me tell you, I’m doubtful whether the makers used actual Mesopotamian scripts here or not, because it looks more like the Zonai script from the video game The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom.

TL;DR – The Moothon–Enki Theory

The people of ancient Mesopotamia, living between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, imagined the world as shaped by a vast family of gods and goddesses (much like the Greeks or Hindus). This pantheon was not just a group of divine figures, but a complex society — with rules, rivalries, leaders, and conflicts.

Understanding this divine family is the first step to understanding the Mesopotamian world — and, perhaps, Moothon’s place within it in Lokah.

Our theory connects Moothon to the Mesopotamian deity Enki, as reinterpreted by Zecharia Sitchin’s “ancient astronaut” theory.

In this view, Moothon is a powerful Anunnaki leader who created and protected humanity, standing against destructive gods like Ishtar. This article breaks down the myths and fringe theories that support this connection — and explains how Lokah might be reworking them.

The Beginning of Creation in Mesopotamian Myth

Before the world existed, myths say there was only water in chaos. From that endless ocean came two mighty forces:

- Apsu – the spirit of fresh water flowing under the earth.

- Tiamat – the spirit of the wild, salty sea.

When their waters met, life began. The first gods were born — younger, restless, and full of energy. But their noise disturbed their parents. This tension set the stage for a cosmic conflict, one that shaped the heavens, the earth, and the world humans live in today.

Anu, the Sky Father

At the very top stood An (called Anu by the Akkadians). He was the god of the sky, the highest authority, and known as the “Father of the Gods.”

- Human kings claimed their right to rule came from him.

- His authority was called anûtu (“Anu-power”).

Yet despite his supreme title, Anu was distant. He lived in the highest heaven, he rarely came down to interfere with gods or humans.

The day-to-day world was instead shaped by more active gods like Enlil. This mirrored Mesopotamian politics: a high king ruling over many city-states, while local governors held real influence.

Who is Enlil?

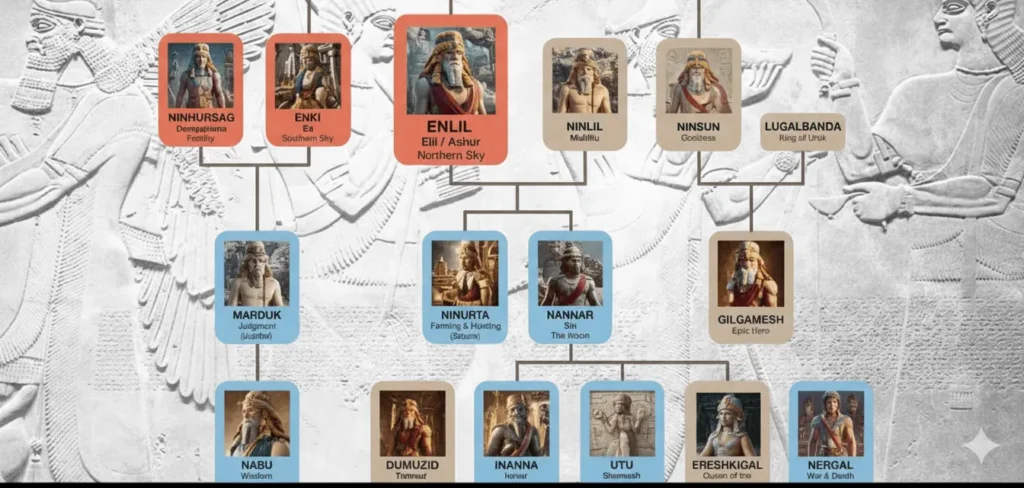

The Anunnaki: The Great Gods Who Gave Orders

The most important gods in mesopotamian myths were the Anunnaki (“those of royal blood”). They were the children and grand children of An (Anu) and Ki (Antu).

Their main role: deciding the fate of humans.

The most famous group was the “seven gods who decide”:

- An (Anu) – god of the sky

- Enlil – god of air and storms

- Enki (Ea) – god of water and wisdom

- Ninhursag (Antu) – goddess of earth

- Nanna (Sin) – god of the moon

- Utu (Shamash) – god of the sun and justice

- Inanna (Ishtar) – goddess of love and war

In early stories, the Anunnaki ruled as high gods in heaven. Later, they became judges of the underworld, showing how beliefs about death evolved.

The Ruling Triad: A Model for Lokah’s Power Struggles?

Even though Anu was the high king of the gods, he did not rule alone. He shared his power with two other great deities, forming what myths describe as a ruling triad.

- Enlil – God of air, wind, and storms. The son of Anu and Ki, he was often the most powerful god in action. While Anu stayed distant, Enlil carried out the decisions of the gods and eventually became the active head of the pantheon.

- Enki (Ea) – God of water, wisdom, and creation. Known for his cleverness, Enki was seen as a friend to humans. He often warned them about the harsh plans of the other gods, like in the story of the Great Flood.

Together, Anu (sky), Enlil (air), and Enki (water) ruled over the three great domains of the universe.

In Lokah, this triad can be seen as a model for hidden cosmic power struggles, where Moothon (like Enki) is the quiet protector, and Ishtar plays the enforcer.

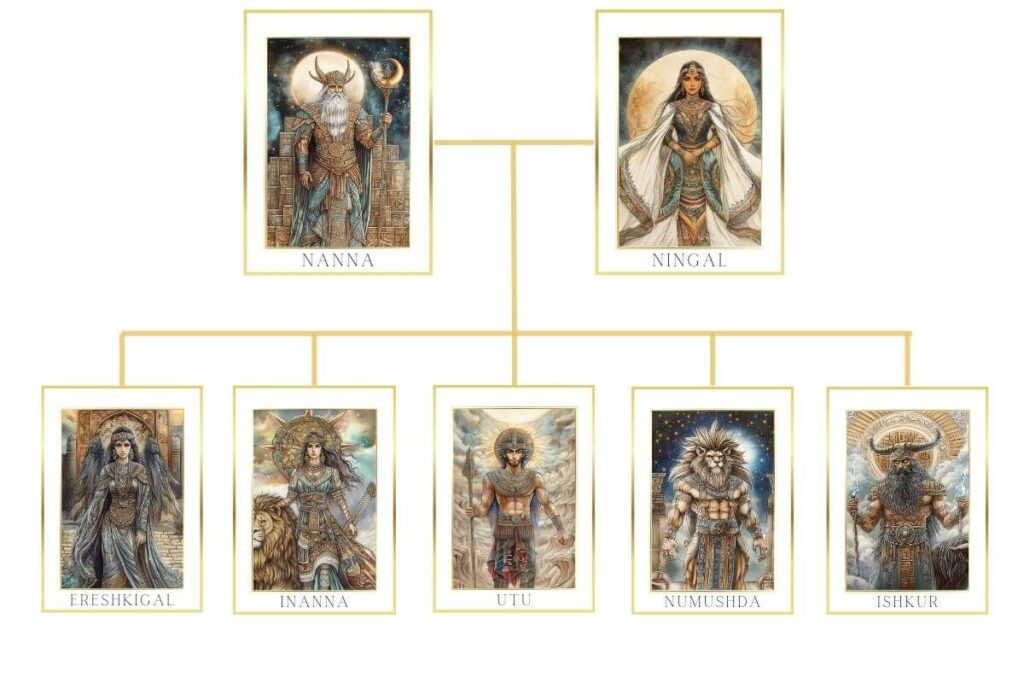

Ningal, the Great Lady, and Nanna, the Moon God

In Mesopotamian myths, one of the most important divine couples was Ningal and Nanna. They ruled over the night sky and the fertile lands, and together their family explained much of how the world worked.

Ningal, the Great Queen

The name Ningal means “Great Lady” or “Great Queen.” She was the daughter of Enki, the god of water and wisdom, and Ningikuga, the goddess of reeds and marshlands. Because of this, Ningal was strongly connected to the wetlands of southern Mesopotamia — the very place where Sumerian civilisation grew. She was the protector goddess of the great city of Ur.

Nanna, the Moon God

Ningal’s husband was Nanna, called Sin by the Akkadians, the god of the moon. He ruled the cycles of the night sky and was linked to the measurement of time, since the months were counted by the phases of the moon.

Like Ningal, Nanna’s main temple was in Ur, and their marriage was celebrated in myth. Stories about their union were told to teach the value of family and marriage in Mesopotamian society.

Their Divine Family

Together, Ningal and Nanna created a family that reflected the natural order:

- Utu (Shamash), the sun god of justice

- Inanna (Ishtar), the goddess of love and war, is linked to the planet Venus. Ishtar was also known as the “Queen of Heaven”.

This family gave people a complete picture of the world. Ningal, born of water and reeds, represented the fertile earth. Nanna, as the moon, ruled the rhythm of the night sky.

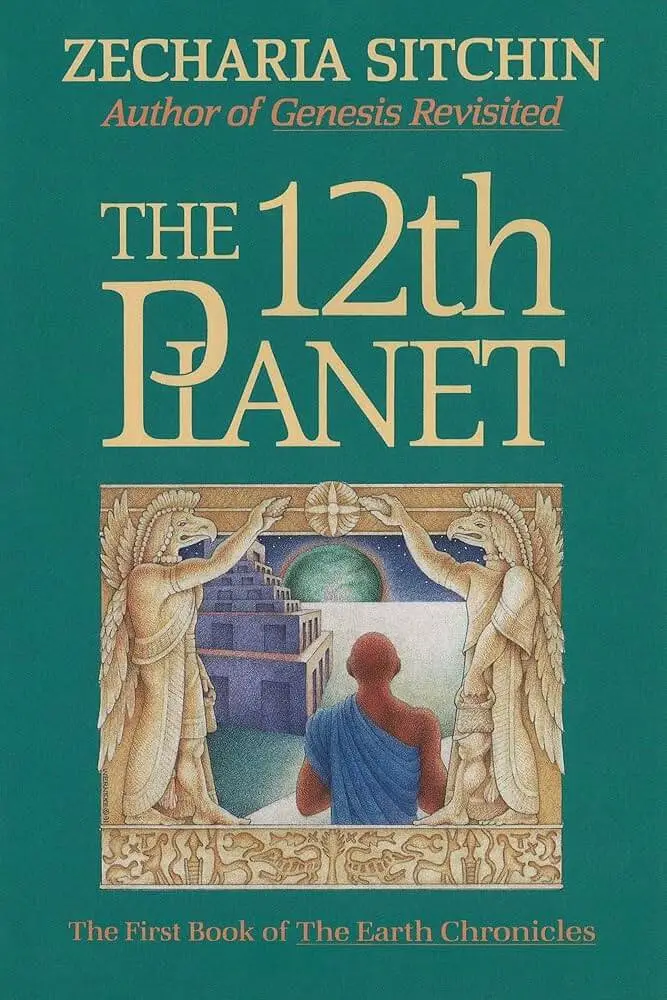

From Myth to Sci-Fi: The Zecharia Sitchin Theory

In Mesopotamian myth, the sky god Anu ruled as the “Father of the Gods.” From his bloodline came powerful deities, and they are the Anunnaki.

Later, Zecharia Sitchin’s book The 12th Planet (1976) spun a radical theory: the Anunnaki were not gods, but aliens from Planet X (Nibiru).

- The Anunnaki were aliens from a hidden planet called Nibiru.

- They came to mine gold to repair their atmosphere.

- When the work became too much, they created humans (mixing their DNA with Homo erectus).

According to Sitchin, humans were not born to worship, but born to work.

Zecharia Sitchin was not a historian, but a writer with a very bold idea. He believed they were just advanced humans from space with technology that looked like magic to ancient people.

Why This Theory Resonates with Lokah

This idea matches Lokah’s tagline: They Live Among Us.

- Moothon as Enki → the one who gave knowledge, always protecting humanity.

- Ishtar as antagonist → bitter and destructive, still hunting.

Lokah reimagines these conflicts through its immortal characters.

Want to know more? It’s too long to read, but worth if you are really interested.

The 12th Planet – Nibiru

According to Sitchin, their home was a hidden planet called Nibiru, which moves around the sun in a very long orbit, taking 3,600 years to come close to Earth. He called it the “12th Planet” if we count the Sun, Moon, and Pluto as planets.

Why They Came to Earth

He claimed the Anunnaki came here 450,000 years ago for a practical reason — to mine gold. They needed it to repair their own atmosphere, by turning the gold into fine dust to protect their planet. This was not about spirituality, but pure survival.

The Creation of Humans

But the work was hard. The Anunnaki workers themselves got tired of digging. To solve this, their leaders created a new species. Sitchin says they mixed their own DNA with that of Homo erectus, an early human. The result was Homo sapiens — us. Not born to worship, but born to work. In his telling, humanity was created as a slave race.

Why It’s Controversial

Sitchin’s story is exciting, but historians do not accept it. His translations of Sumerian texts are disputed, and mainstream archaeology sees the Anunnaki as mythical gods, not aliens. Still, his theory became popular because it mixes myth, science fiction, and conspiracy in one package.

The Gift of Civilization

After creating humans, the Anunnaki did not stop at making miners. They also gave humans knowledge and skills. According to Sitchin, this is why Sumerian civilization appeared so suddenly, with advanced ideas in astronomy, farming, and city life.

The Anunnaki even set up cities and declared themselves as gods. To control people better, they introduced “kingship” — where humans ruled on their behalf, acting as a link between the masses and their alien overlords.

The Great Flood: A Planned Extinction

As humans grew in number, their noise and rebellions irritated Enlil, one of the Anunnaki leaders. Around the same time, a disaster was coming: Sitchin says the orbit of their planet Nibiru would pull on Earth, breaking the Antarctic ice sheet and causing a global flood.

Enlil wanted to use this flood as a chance to wipe out humanity. The council agreed not to warn humans. But Enki, who had helped create mankind, disagreed. He secretly told a loyal human (known as Utnapishtim in Mesopotamian myth, or Noah in the Bible or Matsya Purana from hinduism) to build a huge boat. In it, he saved his family and the seeds of all living things.

As the waters rose, the Anunnaki watched from orbit in their ships.

A New Beginning and the Wars of the Gods

When the waters went down, Earth was empty. The Anunnaki realised they had made a mistake — they still needed humans. So, they helped the survivors rebuild civilisation.

But peace didn’t last. Two factions of the Anunnaki fell into conflict:

- Enlil’s side – strict rulers, focused on order and punishment.

- Enki’s side – scientists and creators, closer to humanity.

These clashes were fought not just with words but with wars over resources and cities. Sitchin even reinterprets old stories like the Tower of Babel as battles between alien factions, with humans used as soldiers in their fights.

Nuclear Calamity and Departure

The conflict reached its worst point around 2024 B.C. One faction used nuclear weapons to destroy the Sinai spaceport and nearby cities like Sodom and Gomorrah, so they would not fall to the enemy.

The Fall of the Anunnaki and the Rise of Moothon

In Sitchin’s story, the nuclear blast of 2024 B.C. changed everything for the Anunnaki.

Enlil: The End of a Reign

Enlil, the commander, was the one who pushed for the nuclear strike, along with his son Ninurta and the council of gods. The plan was simple: stop Enki’s son Marduk from taking over the Sinai spaceport and becoming supreme.

But it backfired. The nuclear cloud — remembered in ancient texts as the “evil wind” — drifted east into Sumer, Enlil’s own land. People died, rivers turned toxic, fields went barren. Sumer collapsed almost overnight, and with it, Enlil’s authority.

The great age of Enlil was over. He and his family had no choice but to leave their ruined cities and scatter.

Enki: The Long Game Pays Off

Enki had opposed the use of nuclear weapons, and though he too saw the destruction as a tragedy, it cleared the path for his side.

His firstborn son Marduk (Ra in Egypt) rose out of the chaos as the strongest.

With Enlil’s cities destroyed and the spaceport gone, there was no one left to block Marduk. The council was forced to recognize his supremacy.

For the first time, the “Enlilship” — the status of chief god — passed to Enki’s line. The long rivalry between the brothers was decided.

Ishtar: The Fallen Queen

Ishtar (Inanna) was tied to Enlil’s clan. She had fought bitterly against Marduk, trying to restore her city Uruk as the center of power. But when Sumer fell, so did her temples, her cult, and her influence.

Her rivalry with Marduk ended in defeat. While Sitchin’s texts don’t give her much detail after the disaster, she was left weakened, just another displaced power in the aftermath.

The Departure of the Gods

Sitchin’s final claim comes in his book The End of Days: after centuries of trying to recover, the Anunnaki eventually left Earth around 556 B.C.

The last temples closed, the myths hardened into religion, and humans were left to run history alone. But the gods promised they would return.

How Lokah Might Use This

Now let’s bring this back to Lokah. The film begins with Ishtar sending assassins to capture Neeli, who is hiding in a burning building, holding something secret. At the same time, we hear Moothon calling Neeli back.

This connects perfectly with Sitchin’s framework:

- Moothon could be Enki, the one who always protected humanity, the giver of knowledge, the voice that calls Neeli home.

- Ishtar, bitter after her defeat, still acts as an antagonist, hunting Neeli just as she once hunted Marduk’s followers.

Final Thoughts – What Do You Think?

Is Moothon really Enki, the protector of humanity? Or is he another hidden figure from Mesopotamian lore?

Share your own Lokah theories in the comments below!

Surely, stories about Enki & Ishtar are fascinating & intriguing. But lokah worked because all characters, whether it is Neeli, Chathan, Kathanar or Odian, are deeply rooted and resonated in Malayali Psyche. Any attempt to introduce “foreign” characters in this story will be suicidal & disaster like Abram Qureshi, who is hanging in the air, without a base

That’s where I got a disconnect with Lokah. Odiyan is not a Ninja Assasin, Neeli is not a vampire, I believe the team just pick the names and the base elements are from west.

Is there any connection between Hinduism and yazidi .From these mythology I think plenty of comparison between mesopotamian gods and Hindu gods.This film is beginning of that tip of the sunken mountain

Muruk is a common thread, Yazidis worship a gaurdian Angel called Muruk,The angel Muruk cave has the painting of a woman lighting a brass lamp (woman wears a sari) and there is a peacock. in Hinduism it is Muruka, and we know lord Muruka also have peacock. Even Gopura style in temple arcchitecture resembles yAZDI temples. According to the Yezidi calendar, it is currently the year 6,764 (which must be number of years they came away from India and started living seperately). Yazdi’s also believe in re-birth.