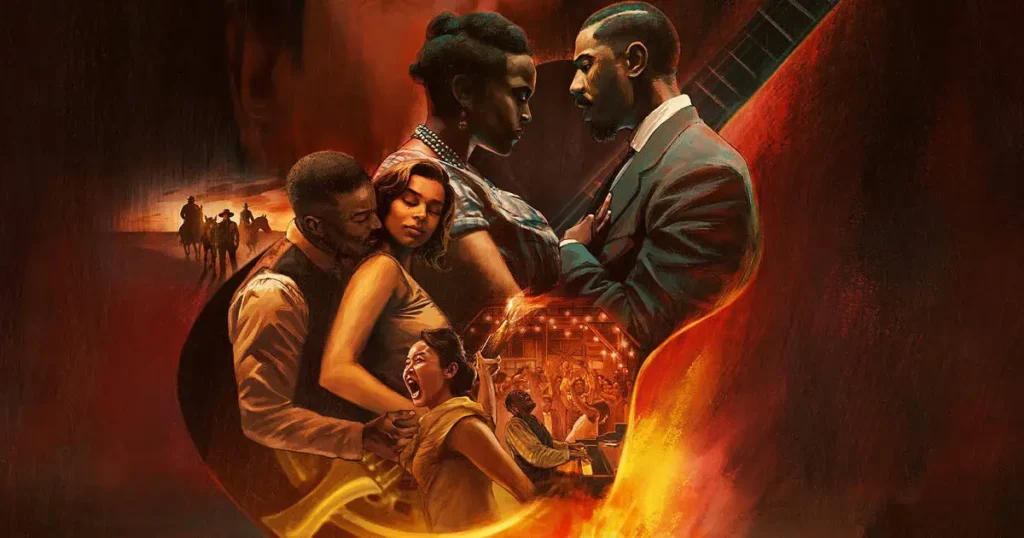

What is the real story behind Dhurandhar? In Dhurandhar several real characters are clearly inspired by real officers, gang leaders, and terror figures, even if their names and details are changed for the screen.

In this article, we break down Dhurandhar — separating cinema from history. We look closely at the Dhurandhar real story, decode the real characters behind the reel roles, and examine which incidents are rooted in fact and which ones are deliberately simplified or dramatized. Not to glorify or accuse — but to understand what the film is really saying beneath the action and patriotism.

Dhurandhar Real Characters: Who Played Whom?

One of the strongest things Dhurandhar does is this: it doesn’t invent heroes and villains out of thin air. Most characters are shaped around real people who operated in the shadows — soldiers, gangsters, intelligence officers, and terrorists whose actions quietly shaped history. The names are changed, but the behaviour, ideology, and outcomes feel very familiar.

Let’s break down the Dhurandhar real characters and understand who they are actually inspired by.

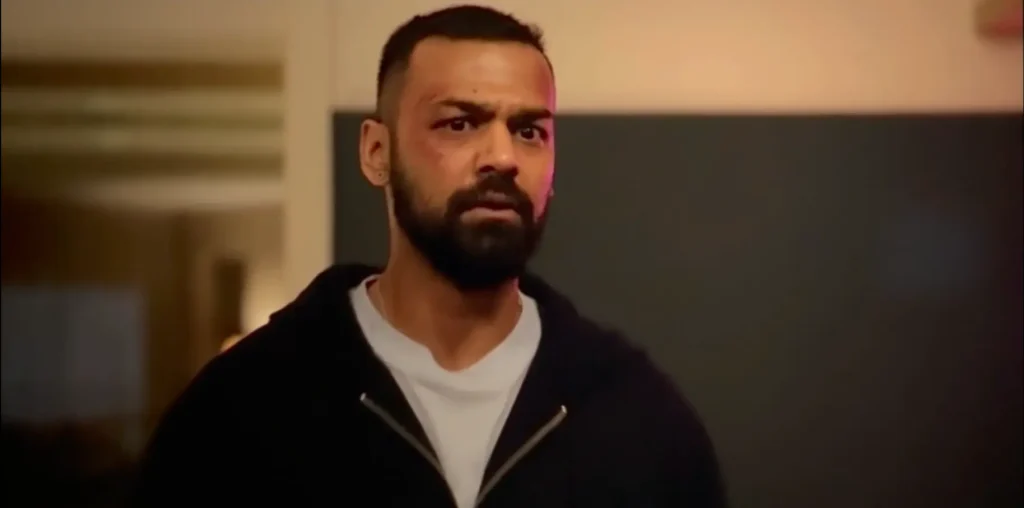

Ranveer Singh as the RAW Agent

(Inspired by Major Mohit Sharma)

The reel character:

Ranveer Singh plays a deep-cover RAW operative who lives with anger, patience, and restraint at the same time. He is not shown as a loud patriot or a chest-thumping hero. Instead, he is quiet, methodical, and willing to disappear into the enemy’s world if that’s what the mission demands. His goal is simple — correct what he believes was a national failure.

The real story behind it:

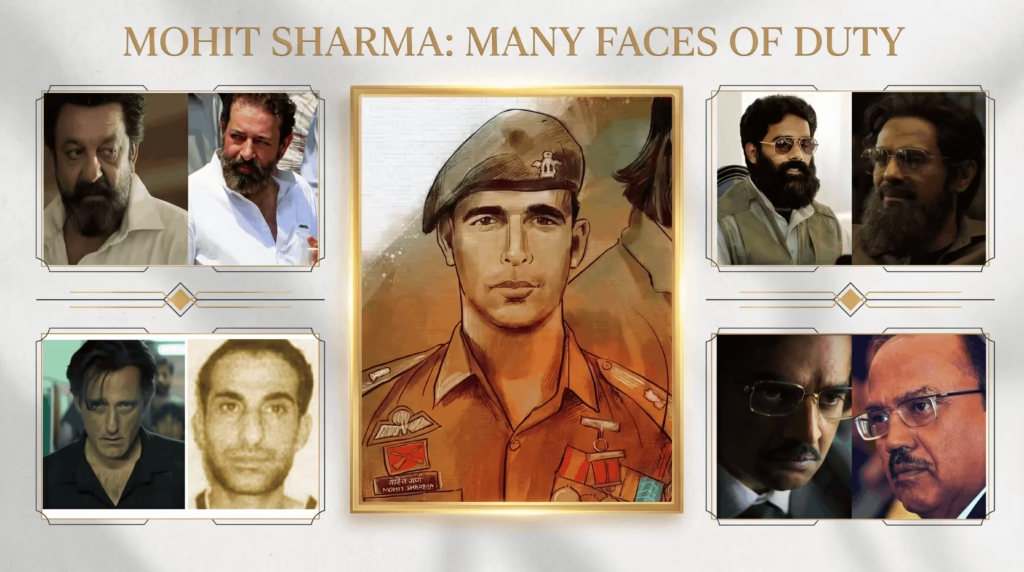

This character draws clear inspiration from Major Mohit Sharma, one of India’s most respected special forces officers and an Ashok Chakra awardee.

Major Sharma infiltrated the Hizbul Mujahideen by taking on the identity of Iftikhar Bhatt. He lived among militants, earned their trust, gathered intelligence, and eliminated key terrorists from inside the network.

In 2009, during an operation in Kupwara, he was critically injured but continued fighting, saved two of his teammates, and killed four terrorists before being martyred. Dhurandhar doesn’t recreate his life exactly, but it captures the core idea — deep infiltration, moral isolation, and sacrifice without recognition.

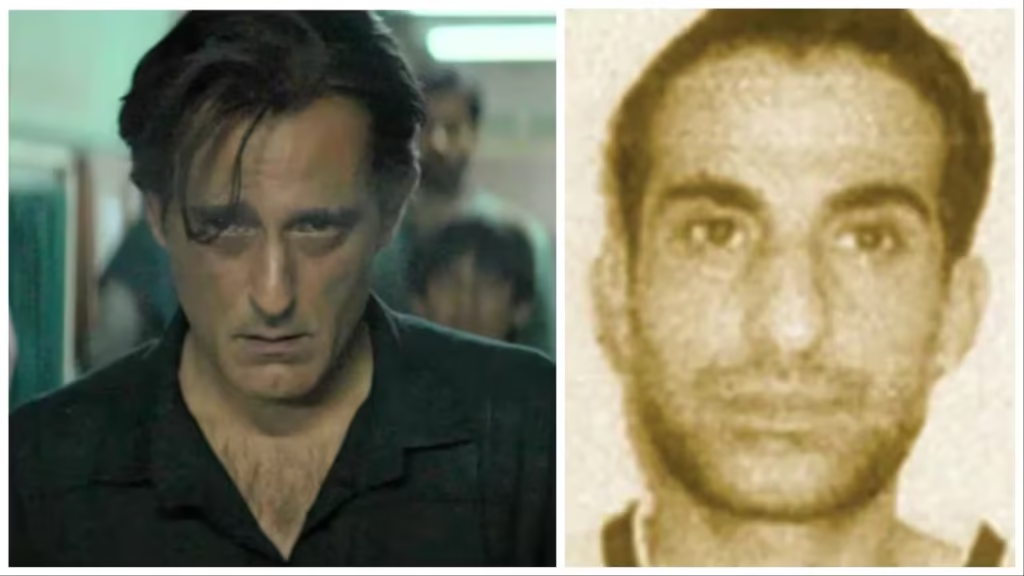

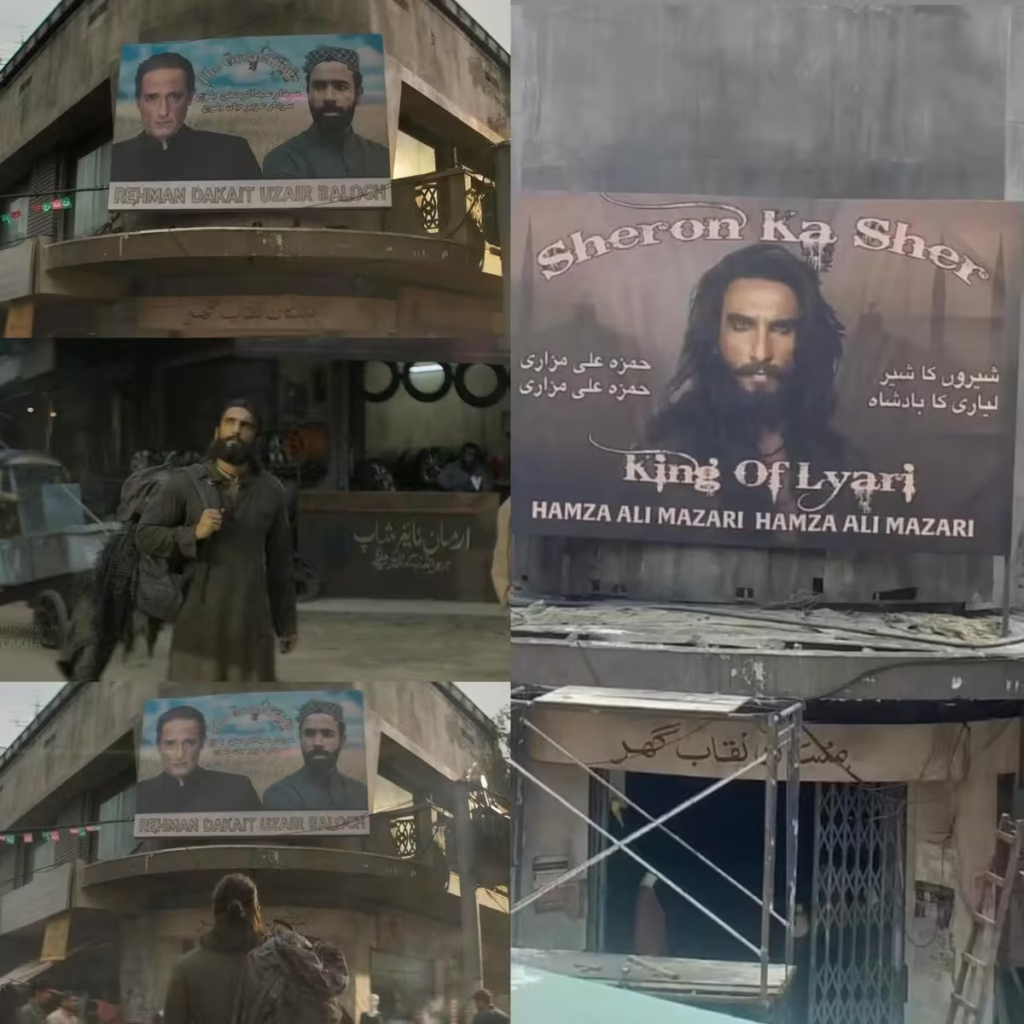

Akshaye Khanna as Rehman Dakait

The reel character:

Akshaye Khanna plays Rehman Dakait as calm, intelligent, and terrifyingly practical. He doesn’t shout. Doesn’t rush. He runs Lyari like a system — controlling crime, politics, and terror logistics as one operation. On the ground, he is the film’s most visible villain.

The real story behind it:

Rehman Dakait was not fictional. His real name was Sardar Abdul Rehman Baloch, and he was one of the most feared gang leaders in Karachi. He rose from petty crime to running Lyari’s underworld, controlling extortion, kidnappings, arms, and protection rackets. For years, Lyari functioned almost like a parallel state.

Like in the film, he tried to move closer to legitimacy by forming the People’s Aman Committee and building political connections. His death in 2009, in a police encounter, remains controversial — many believe he outlived his political usefulness. The film stays close to this arc without naming names.

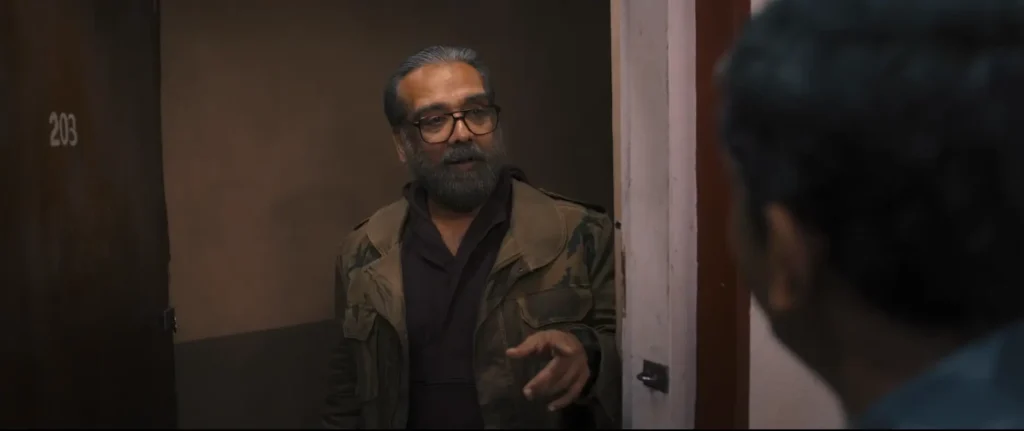

Sanjay Dutt as SP Chaudhary Aslam

(Inspired by Chaudhry Aslam Khan)

The reel character:

Sanjay Dutt plays a hardened Pakistani police officer who is not aligned to gangs, terrorists, or ideology. His loyalty is only to order. He hunts everyone — criminals, extremists, and political pawns — making him dangerous and unpredictable for all sides.

The real story behind it:

This character is almost a direct reflection of Chaudhry Aslam Khan, widely known as Pakistan’s toughest cop. As the head of Karachi’s anti-terror operations, he went after gangsters like Rehman Dakait and Taliban operatives with equal force.

He survived multiple assassination attempts. After a bomb attack on his home, his response was simple: “I will bury the attackers in the same rubble.” In 2014, he was killed in a suicide bomb attack. His death showed how deeply he had unsettled powerful networks.

R. Madhavan as Ajay Sanyal

(Inspired by Ajit Doval)

The reel character:

Madhavan plays the strategist — not the man pulling the trigger, but the one deciding when the trigger must be pulled. He represents the shift in thinking inside India’s security establishment: from restraint to retaliation.

The real story behind it:

The inspiration here is clearly Ajit Doval, India’s National Security Advisor and former RAW officer. Doval was directly involved in the IC-814 hijacking negotiations and later became the face of India’s aggressive counter-terror doctrine.

From surgical strikes to Balakot, his philosophy has been consistent — threats must be neutralised at their source. The film borrows his worldview more than his biography, using Madhavan’s character to voice that strategic shift.

Arjun Rampal as Major Iqbal

(Inspired by Ilyas Kashmiri)

The reel character:

Arjun Rampal plays the invisible villain — the handler, not the foot soldier. He represents state-backed terror, using criminals and extremists as tools rather than allies.

The real story behind it:

This role is inspired by Ilyas Kashmiri, a former Pakistani soldier who became one of Al-Qaeda’s most dangerous operatives. He was linked to multiple terror plots, including the 2008 Mumbai attacks, and was considered a master of guerrilla warfare.

Once described as a successor-level figure to Osama bin Laden, Kashmiri was reportedly killed in a US drone strike in 2011. In Dhurandhar, his character symbolises the system that enables terror — not just the men who carry it out.

The Real Story vs the Reel Story of Dhurandhar

The IC-814 Hijacking (1999): The film opens with the humiliating memory of India releasing captured terrorists, including Masood Azhar, in exchange for the lives of passengers on a hijacked plane. This event serves as the protagonist’s core motivation—a national shame he is desperate to avenge.

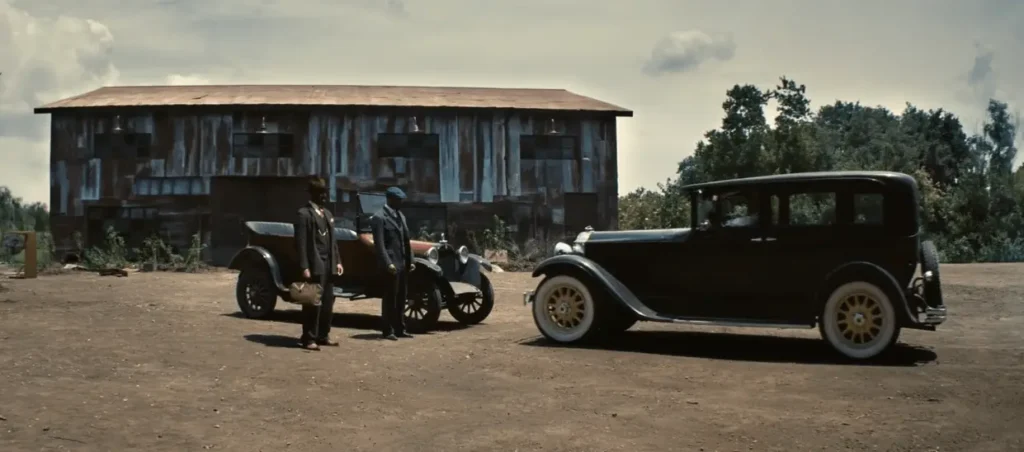

Operation Lyari: A significant portion of the film is set in the volatile Lyari district of Karachi, a lawless region ruled by powerful gangs. This is not a fictional backdrop; it’s based on the real Lyari gang wars that held Karachi hostage for years.

Fact vs fiction:

The emotional impact shown in the film is accurate. But the real event was far messier. Governments were under extreme pressure, options were limited, and every decision carried consequences. The film simplifies this into a clear moral trigger, while reality offered no clean answers.

The Heart of Democracy Under Siege: Parliament Attack (2001)

The real story:

On December 13, 2001, five terrorists linked to Jaish-e-Mohammed attacked the Indian Parliament. Using a vehicle with fake security markings, they breached the complex and opened fire. The encounter killed nine security personnel and a gardener. All five attackers were neutralised.

The Dhurandhar version:

The film does not recreate the attack in detail. Instead, it uses it as proof. In briefings and conversations, the Parliament attack is referenced as evidence that restraint had failed. That release in 1999 was followed by escalation, not peace.

This is where Madhavan’s character gains authority in the narrative. The old logic — patience, restraint, diplomacy first — is shown as outdated. The film positions this attack as the moment where covert retaliation becomes inevitable.

Fact vs fiction:

The connection between Kandahar and later terror attacks is real. But history is rarely linear. The film compresses years of intelligence failures, global politics, and regional instability into a straight line to make its argument clearer. It’s a simplification — but a deliberate one.

The 26/11 Connection That Changes Hamza’s Mission

How 26/11 is Referenced in the Movie:

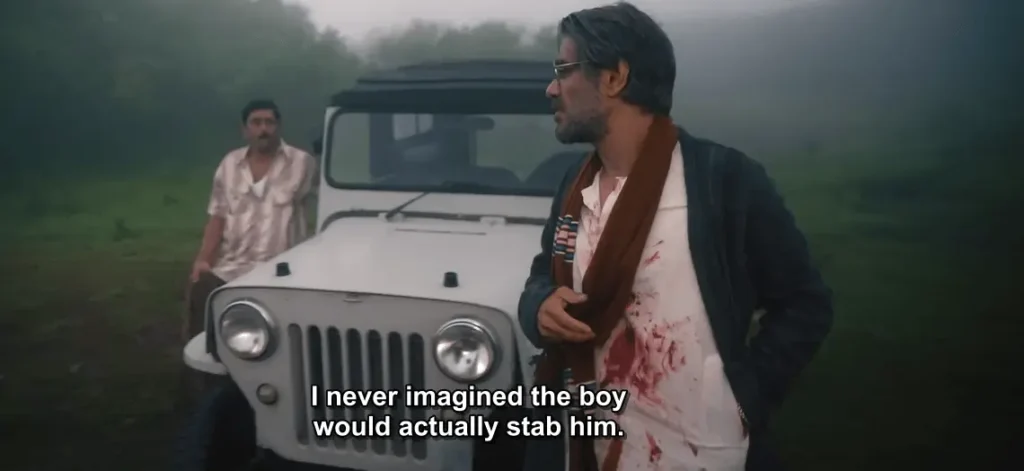

The 26/11 attacks become the emotional and moral catalyst for Hamza’s betrayal of Rehman Dakait. Here’s the pivotal moment:

Hamza discovers that the weapons supplied by Rehman Dakait to various terror groups were used in the 26/11 Mumbai terror attacks.

This revelation is deeply disturbing to Hamza because it shows that his mentor—the man he worshipped as the “Sher-e-Baloch” (Lion of Balochistan), who claimed to fight for Baloch upliftment through schools, hospitals, and jobs—was actually complicit in terrorism that killed innocent civilians in India.

The Breaking Point:

When Hamza witnesses Rehman celebrating with ISI chief Major Iqbal after the “success” of the 26/11 attacks, something inside him shatters. This is the moment when Hamza’s loyalty transforms into hatred.

He realizes that Rehman has betrayed not just India, but his own people—the Baloch community he claimed to serve. Rehman has become nothing more than a puppet of the ISI, using terror to advance Pakistan’s strategic interests.

The Moral Justification:

This discovery provides Hamza with the moral justification he needs to execute his mission. He’s no longer just following orders from Ajay Sanyal; he’s now driven by a personal vendetta. Rehman’s involvement in 26/11 makes him, in Hamza’s eyes, a legitimate target who deserves to die.

The Economic Jihad: The De La Rue Fake Currency Scandal

The real story:

This is the least discussed, and arguably the most uncomfortable part of the film’s inspiration. For years, Pakistan’s ISI pushed high-quality counterfeit Indian currency into circulation. This wasn’t street-level forgery — these were “supernotes” almost impossible to detect.

The controversy deepened when allegations emerged that a British security printing firm, De La Rue, had supplied technology to both India and Pakistan.

Investigations later raised questions about decisions taken during the UPA era — monopoly contracts, ignored warnings, and extended agreements despite security concerns. The implication was disturbing: India’s economic security may have been weakened not only from outside, but also through internal policy failures.

In simple terms, fake currency funded terror, and systemic decisions allegedly made that easier.

The Dhurandhar version:

The film strips this story down. It shows fake currency as a Pakistani operation run through gang networks and ISI handlers. The focus stays external. There is no mention of questionable contracts, corporate responsibility, or Indian administrative failures.

From a storytelling perspective, this makes the narrative cleaner. Villains stay on one side. The system remains intact.

Fact vs fiction:

This is where the gap is widest. By avoiding the role of internal vulnerability, the film removes the most disturbing part of the real story.

The truth was not just about an enemy printing fake notes — it was about how fragile systems can be when oversight fails. Dhurandhar turns a story of institutional weakness into a familiar spy-versus-villain framework.

Dhurandhar Ending Explained: The Rise of a King, The Birth of a Monster

The Twist That Changes Everything: Who is Hamza Ali Mazhari?

Just as you’re processing Hamza’s ruthless ascent to power, the film delivers its most devastating blow. In the final moments, we learn the truth:

Hamza Ali Mazhari does not exist.

He is a carefully constructed identity, a mask worn by Jaskirat Singh Rangi, a death-row inmate from India.

Recruited by IB Director Ajay Sanyal (R. Madhavan), Jaskirat was given a new face, a new name, and a new life for a single purpose: to infiltrate Pakistan’s deepest terror networks and dismantle them from within. He is the ghost in India’s first-ever covert espionage operation of this scale.

This revelation is the key to the entire film. It reframes everything we’ve seen.

Hamza’s loyalty, his internal conflicts, his moments of brutality—they are all part of a deep-cover role played by a man who has sacrificed his very identity for his country.

The Ranveer Singh real identity Dhurandhar twist isn’t just a clever plot device; it’s a commentary on the profound psychological toll of espionage. To become the perfect monster, Jaskirat had to bury the man he once was.

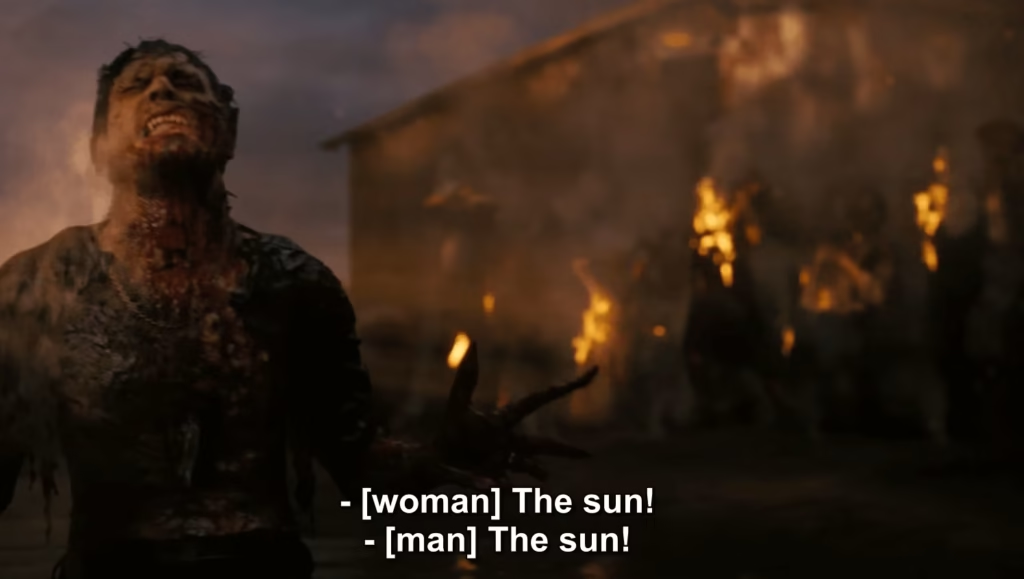

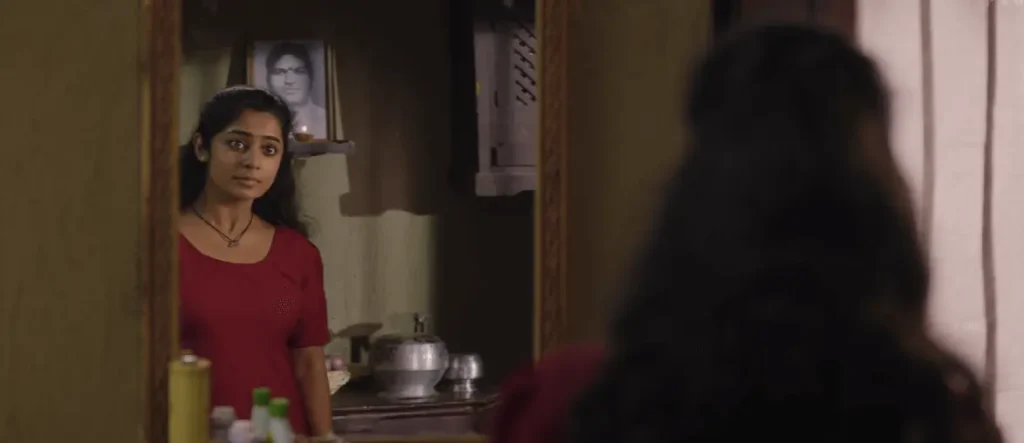

The Ending Isn’t Victory — It’s Consequence

After eliminating Rehman and taking control of his empire, Hamza/Jaskirat (Ranveer Singh) is not shown celebrating power. Instead, he is disturbed.

He sees Rehman everywhere — in reflections, in silence, in memory. These are not literal ghosts. They are reminders.

He has become what he was sent to dismantle.

This is where Dhurandhar becomes uncomfortable. Jaskirat didn’t just defeat a system — he absorbed it. He now carries its violence, its logic, its moral weight. The mission succeeded, but the man did not remain intact.

The final moments push this further.

Hamza turns his attention to the real architect behind everything — Major Iqbal (played by Arjun Rampal), known within the system as “Bade Sahab.” The post-credits scene makes one thing clear: Dhurandhar Part 2 is not about expanding scale — it’s about escalation.

But the real conflict is internal.

Can Jaskirat continue this mission without fully losing himself? Or has he lived as Hamza for so long that there is no Jaskirat left to return to?

What Dhurandhar Is Really Saying

The ending of Dhurandhar does not celebrate triumph. It questions it.

The film asks something deeper than politics or patriotism:

When a nation sends a man into darkness to fight monsters, what happens if he survives — but comes back as one?

That is the true cost Dhurandhar leaves us with.