If you walked into SPA(2026) expecting a typical adult comedy or som thrills, you probably walked out feeling disappointed — but also thinking. And that’s exactly why I wrote this observations on Abrid Shine’s 2026 malayalam movie SPA. Spa quietly observes people. It holds up a mirror. And sometimes what we see in that mirror isn’t very comfortable. On the surface, it’s just a day inside a spa. But if you sit with it, you realise it’s one of the sharpest social satires Malayalam cinema has done in recent years….not about sex, but about hypocrisy, desire, and the gap between who we pretend to be and who we actually are.

This isn’t a typical movie review for Spa (2026). Think of it as trying to understand what Abrid Shine was really doing with this experiment.

The Rejection of Narrative: A Film Without a Graph

Spa is a film that, from its very first scene, tells you to abandon all preconceived notions of conventional cinema.

There is no three-act structure, no clear protagonist, no rising action, no central conflict, and certainly no neat resolution in the end.

Instead, Shine invites us into the closed, intimate world of a spa in Kochi, and for two hours, we become voyeurs, observing a series of episodic encounters that expose the raw, often uncomfortable, truths about desire, morality, and the hypocrisy that governs our society.

The spa itself becomes the main character.

This structure is very important because if the film followed one person’s story, we would focus on their drama. Even there is a director character who asks a therapist, “What is your story?” She says, “Our story is boring. We come, we do massages, we go — nothing exciting. But the people who come here make it exciting.” Abrid Shine follows the same philosophy here.

And slowly you realise: this isn’t about individuals. It’s about behaviour.

The film doesn’t just talk about hypocrisy. It shows it happening again and again until you can’t ignore it.

How SPA Flips the Male Gaze

When we think a bout a cinema with title, the first thought might be objectifying women with semi nudity and some jiggling moments in the dark rooms. SPA quietly flips that idea.

Here, the camera isn’t interested in objectifying women. The women are mostly fully dressed, calm, professional, and in control.

It’s the men who are exposed — physically and emotionally.

We meet a sawmill worker, a doctor, an artist, and even a film star, each bringing their own unique set of desires, insecurities, and moral contradictions into the therapy room.

They lie on massage tables, vulnerable, stripped not just of clothes but also of their social masks. The respected doctor, the tough officer, the intellectual poet — inside the spa they all look the same. Just men dealing with desire, insecurity, and ego.

The camera never sensationalises nudity. Instead, it observes behaviour.

That choice makes a big difference because the film isn’t trying to shock — it’s trying to study the male psyche.

And that’s where the satire becomes sharp. Let me explain that with few examples from Spa.

The Innocent Hypocrite

Mathan looks harmless, almost sweet. He’s inexperienced with women and slowly becomes emotionally attached to his therapist. He feels protective, like a “nice guy.”

But the irony is obvious. He’s still part of a system he might morally judge if it involved someone from his own family.

His innocence isn’t pure — it’s blind. And that’s what makes his character interesting. The conversation between Mathan and therpaist Riya is one of the peak moments in the cinema.

Unfortunately, society celebrates these type of characters as protectors. I am sure, after OTT release of Spa, Mathan will be celebrated in reels.

The Many Faces of Male Ego

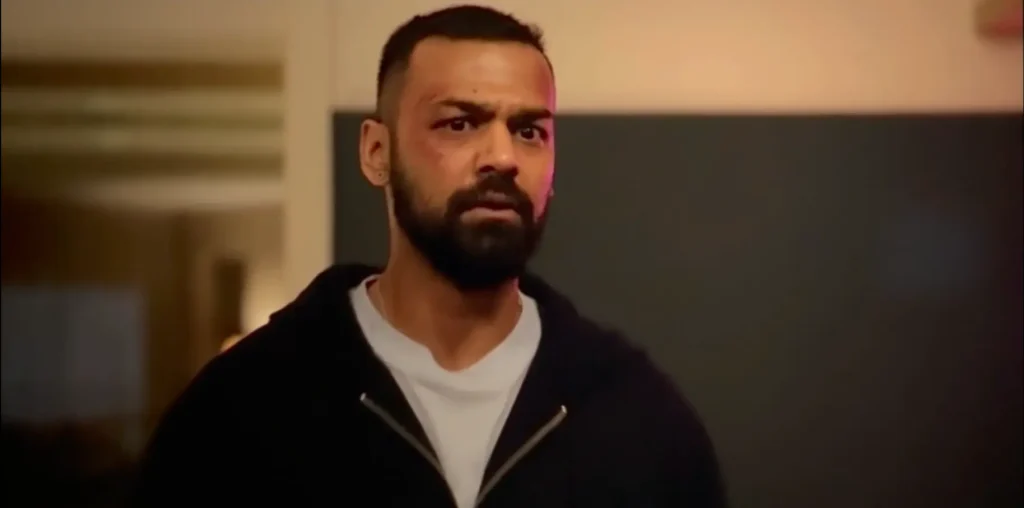

Rahul Madhav’s character represents what you could call a fragile ego. He’s a film star who wants to be recognised but at the same time wants to stay anonymous, which perfectly shows the strange paradox of modern celebrity life.

He wants validation, but he’s also clearly afraid of being exposed, like his confidence is something he constantly has to perform rather than naturally feel.

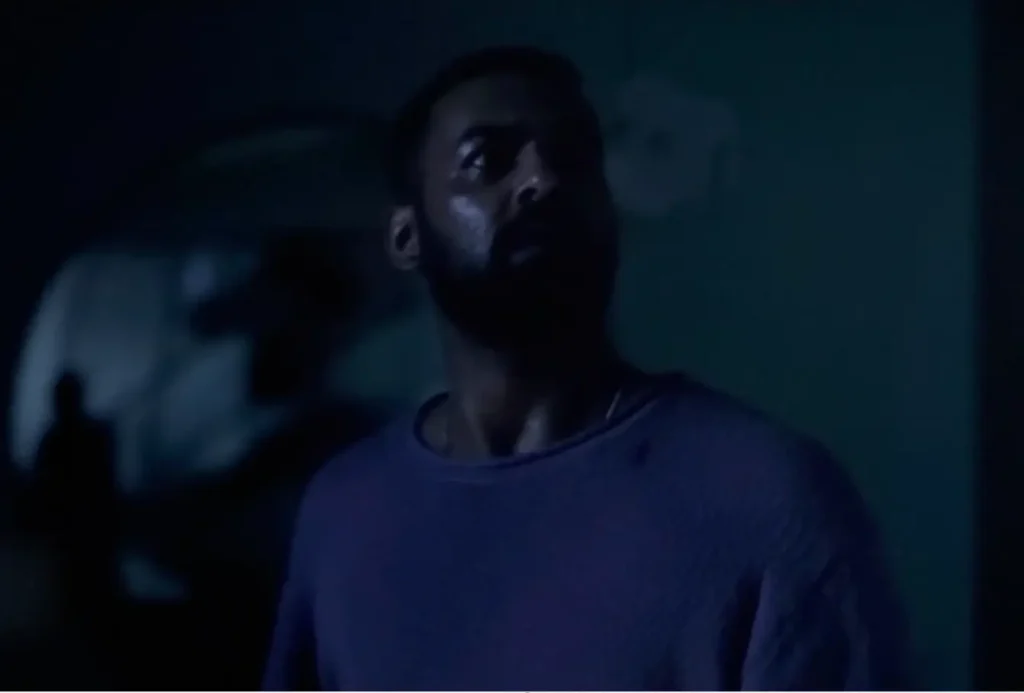

Then there’s Srikanth Murali, who is usually seen in respectable roles like a doctor or advocate, but here he plays a character who is completely stripped of that public dignity.

His performance feels brave because it’s uncomfortable to watch, and in many ways, his character becomes the most direct reflection of what the film is really trying to say about hypocrisy and the gap between public image and private reality. Whole theatre went on shock when he said the word “Ecstacy!!!”

Dinesh Prabhakar’s character feels like a sharp satire of the so-called cultural elite. He comes in as a Malayalam poet carrying all that intellectual weight and sophistication, but slowly his strange and almost comical kinks start to show.

The film subtly shows how he uses his intellect almost like a mask to hide his basic desires, reminding us that education or artistic sensibility doesn’t automatically make someone morally superior — hypocrisy can exist just as easily behind polished words.

What Do the Women of SPA Represent? Professionalism Over Victimhood

Perhaps the most progressive and important choice Abrid Shine makes is in the portrayal of the women.

The film steadfastly refuses to make them victims. We are not given tragic backstories or forced to pity them.

As Radhika Radhakrishnan’s character powerfully states, “If those who seek these services do not have a moral conundrum, why should we?”

Shruthy Menon leads the pack with a commanding presence. She is a seasoned professional, handling difficult clients with a calm authority that comes from experience. She is not a victim; she is a manager.

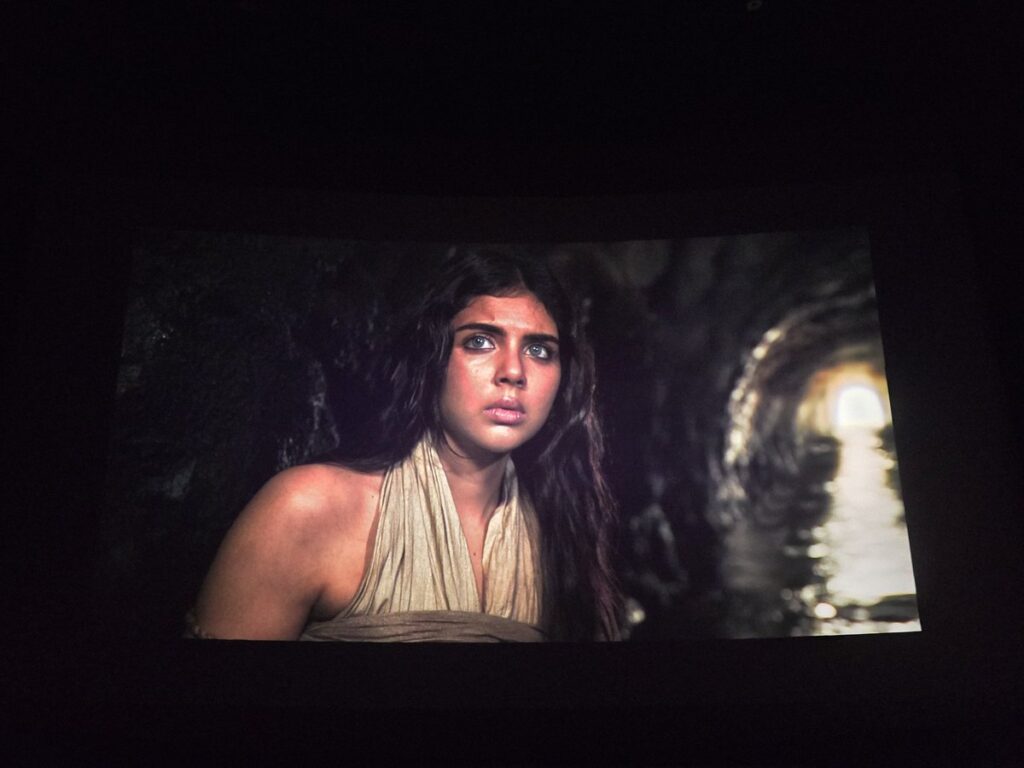

Radhika Radhakrishnan, in a performance that showcases her incredible range, is the emotional anchor for many of the vignettes. Her ability to transition from gentle empathy with Mathan to righteous anger when a client crosses a line is remarkable.

This is the same actress who gave a deeply nuanced and vulnerable performance as the long-suffering mistress in Appan. In SPA, she sheds that vulnerability to embody a woman who is in complete control of her emotional and physical boundaries. The contrast proves her versatility and courage as a performer.

Even Rima Dutta as a calm, soft North Indian therapist, Sreeja Das as Betty, Poojitha Menon and Sree Lakshmi Bhatt as receptionists, Abee Suhana as Monica (as a model), Megha Thomas as sanskari mommy, all did their part well.

Is It a Happy Ending? A Sudden Break in a Carefully Constructed World

After building a quiet, character-driven tone, the film suddenly moves into an action-style climax.

Suddenly, new characters enter, and the film shifts into something that feels like a Kill Bill-style action sequence. The change is so abrupt that it feels slightly out of place.

For nearly two hours, the film carefully builds a realistic world… yes, it’s satirical, but it still feels grounded and observational. Then this sudden move into a spoofy, hyper-stylised climax feels almost like the film loses its confidence.

I felt Abrid Shine’s that choice feels contradictory because the whole film had earlier questioned the need for a traditional story arc in the first place.

Some viewers might interpret this ending as one final satirical comment on filmmaking itself, but emotionally it weakens the impact.

In the end credits, I love the way Abrid Shine roast those taglines “Family movie”, “Award Films”, “Artisctic Social Responsibility film”.

Why SPA is Must Watch Despite Its Flaws in Ending

Even with that uneven ending, SPA remains a bold film.

It trusts the audience to think instead of spoon-feeding emotions. Spa explores desire without judgement. It questions morality without preaching.

By reversing the gaze, presenting women as professionals, and showing repeated patterns of behaviour, the film creates a powerful commentary on society.

More than anything, it starts conversations. Because it asks us to look at ourselves without filters.

It challenges our ideas about morality and respectability. And most importantly, it proves that sometimes cinema doesn’t need a story — just observation.

If you’re willing to engage with it patiently, SPA becomes less of a movie and more of a reflection.